The extension of the amicable settlements in April 2011 in Belgium gave rise to two possible explanations. One explanation claims that a trio of Kazakh oligarchs – Patokh Chodiev, Alijan Ibragimov and Alexander Mashkevitch – used their connections to then French President Nicholas Sarkozy to get away with an ongoing criminal investigation in Belgium by changing the Belgian law on criminal settlements.

The alternative explanation of events claims that the law voted by the Belgian parliament is mostly the result of the diamond traders’ lobby in Antwerp, and of the prosecutors’ interest in having a new – and, according to them, better – legal instrument for tackling corruption.

The first explanation was named “Kazakhgate.” The second, “Diamondgate.” After more than six years since the law on amicable settlements was voted, and after almost 10 months since an inquiry commission was established to investigate the facts, we can evaluate both these explanations based on the proofs that support them. And this evaluation doesn’t look good for Kazakhgate.

Kazakhgate. Evidence from Etienne des Rosaies

The Kazakhgate affair began in October 2012, when the French magazine Le Canard Enchainé first published an investigation allegedly revealing how France interfered with the Belgian legislative process on behalf of Patokh Chodiev and his asociates.

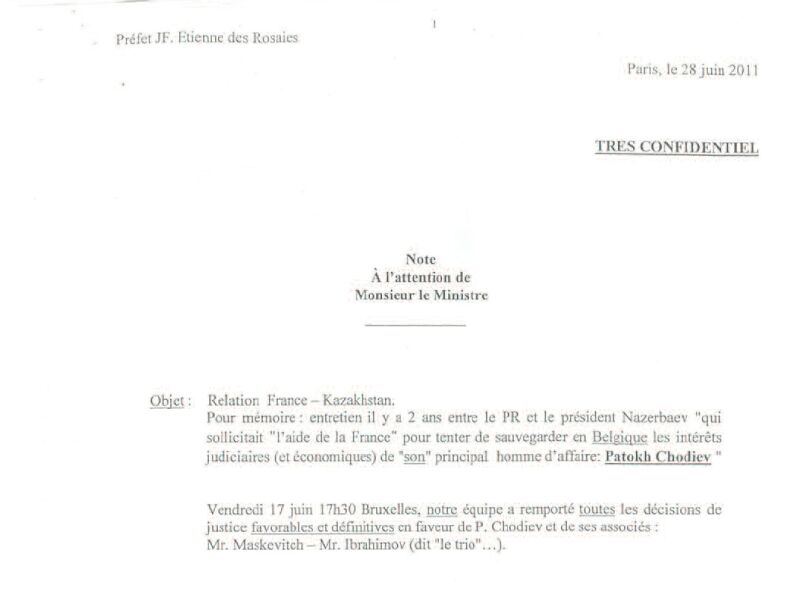

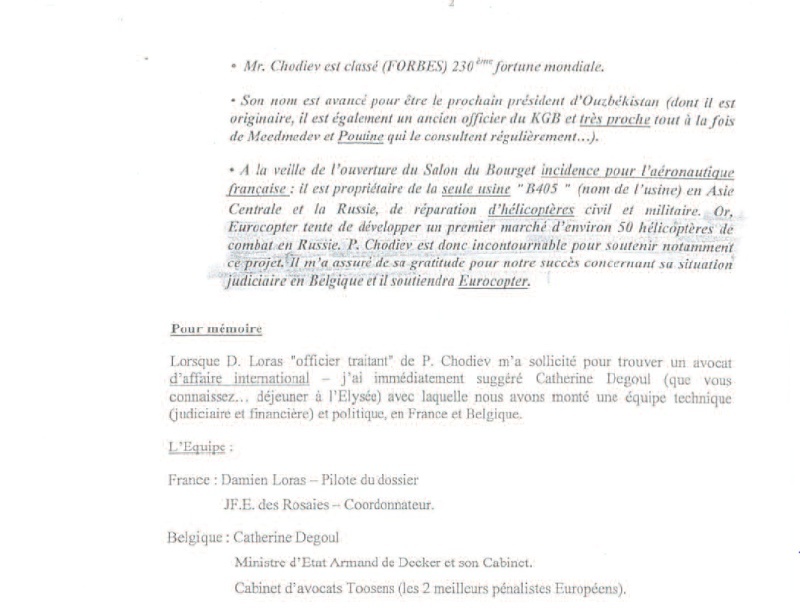

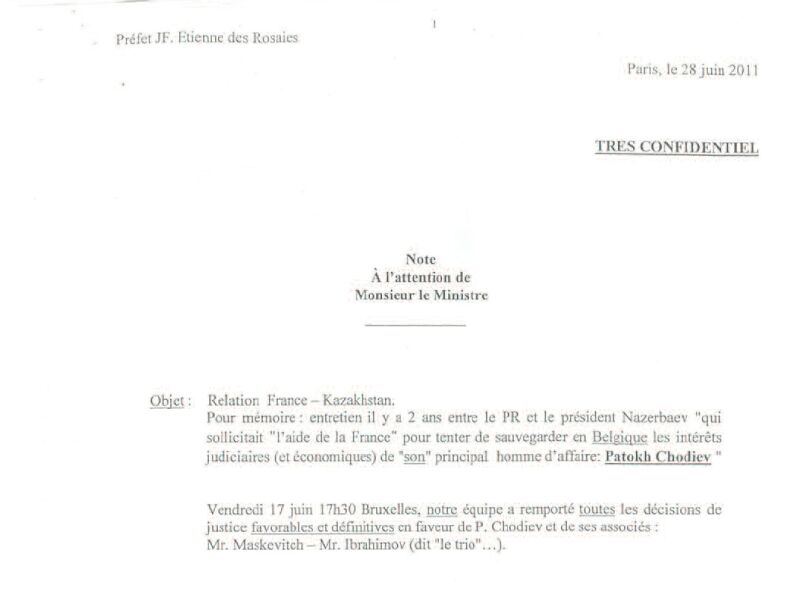

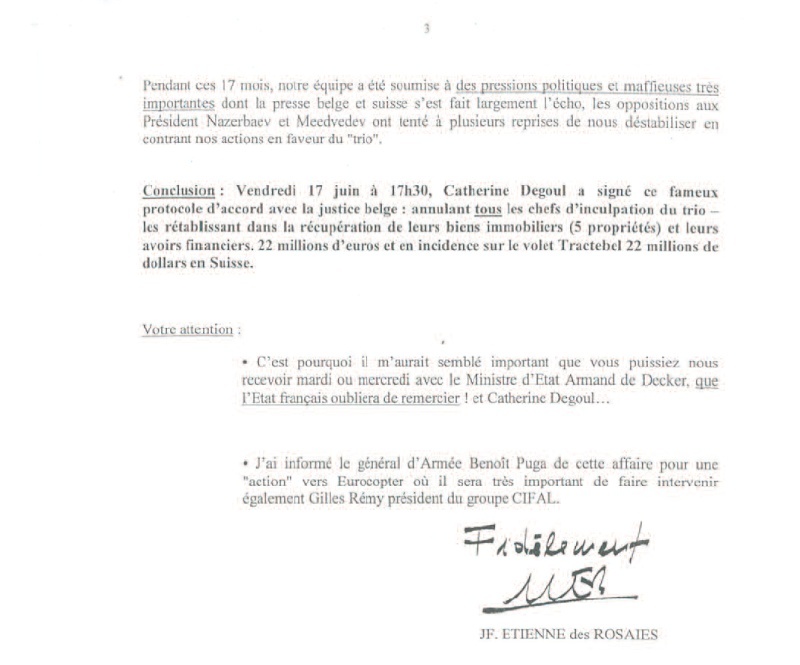

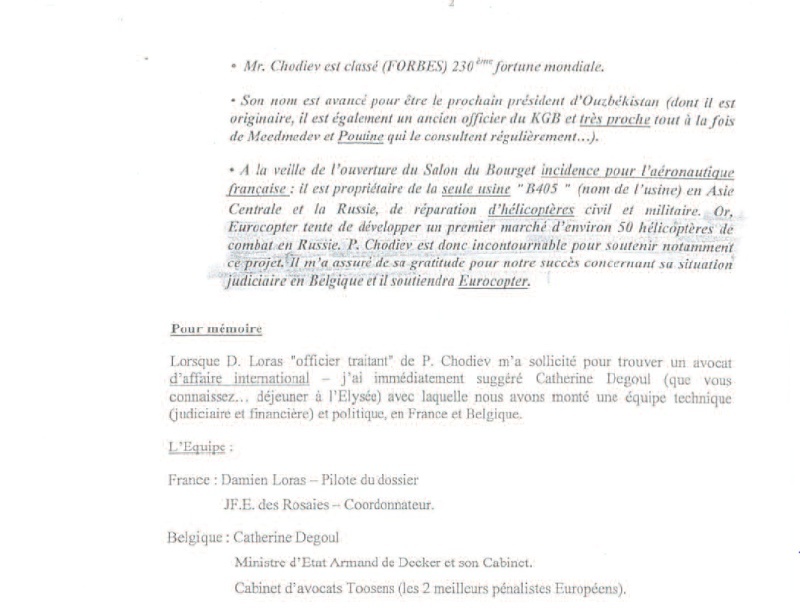

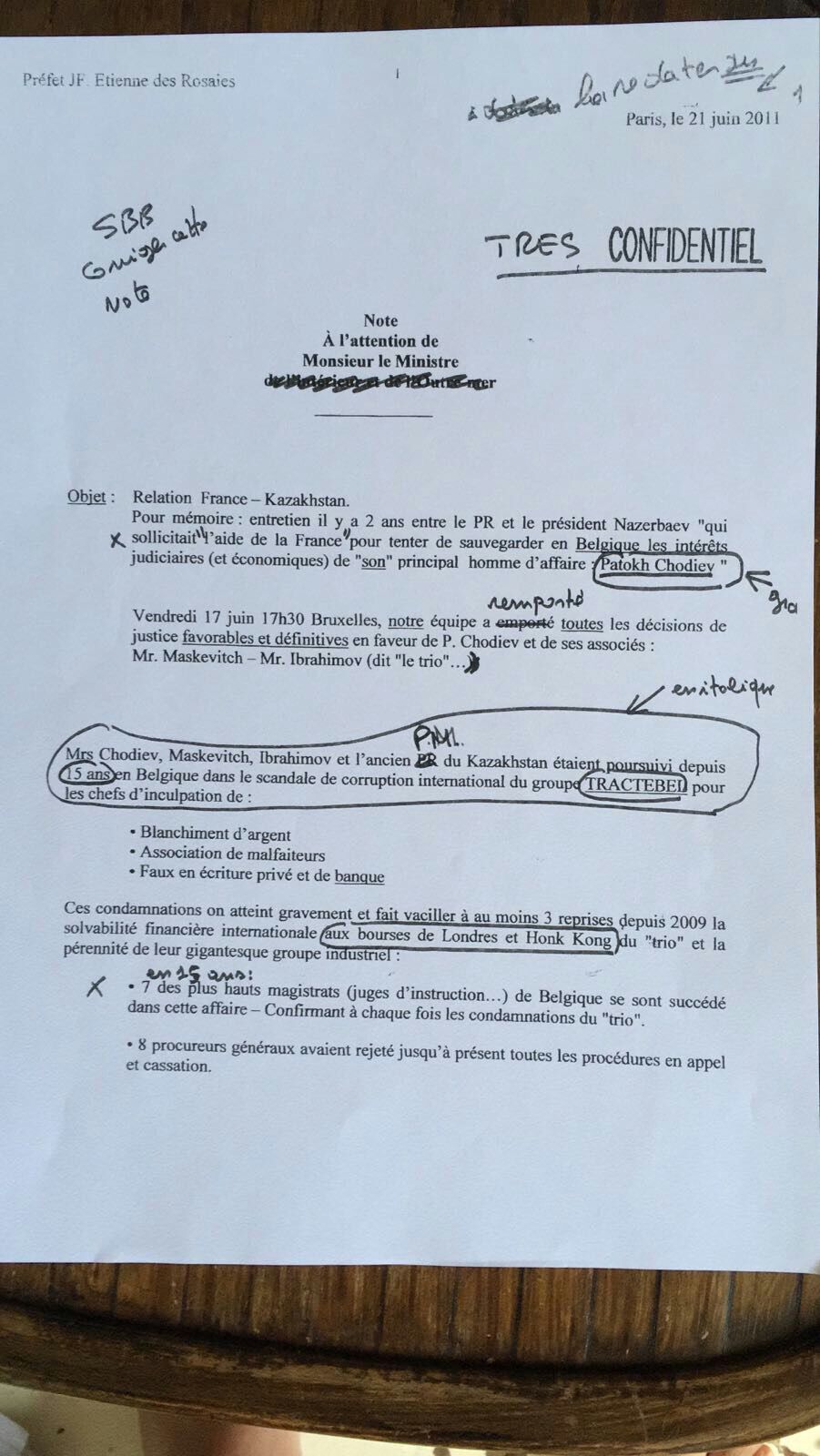

The evidence for that was a note, dated 28 June 2011, written by Jean-François Etienne des Rosaies, a person close to Sarkozy’s inner circle.

The first problem with this note is its date. 28 June 2011 is

after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). In other words, it is a post-factum document.

The other problem is that the note is considered a forgery by Armand De Decker and des Rosaies’ lawyers, so its authenticity cannot be proven beyond reasonable doubt. De Decker even has a written statement from des Rosaies saying that the note is a forgery.

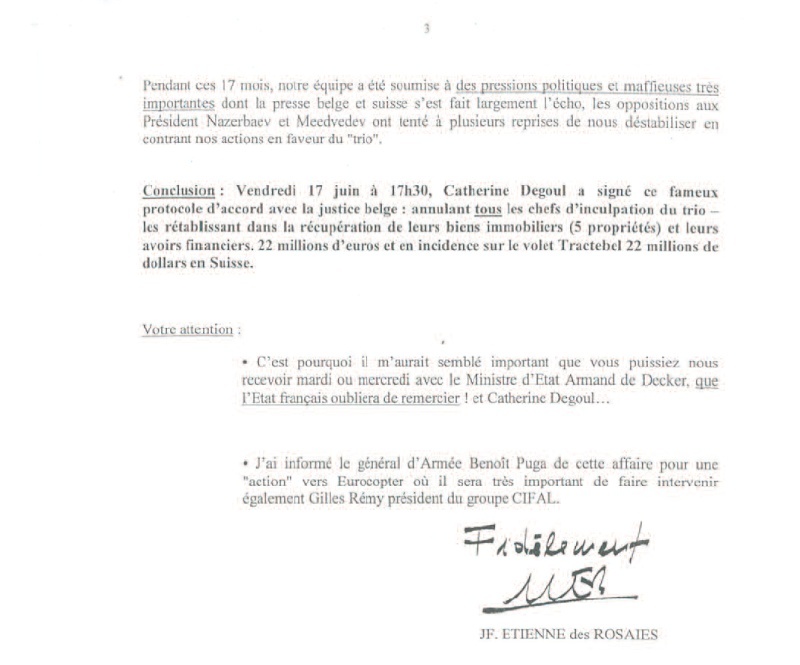

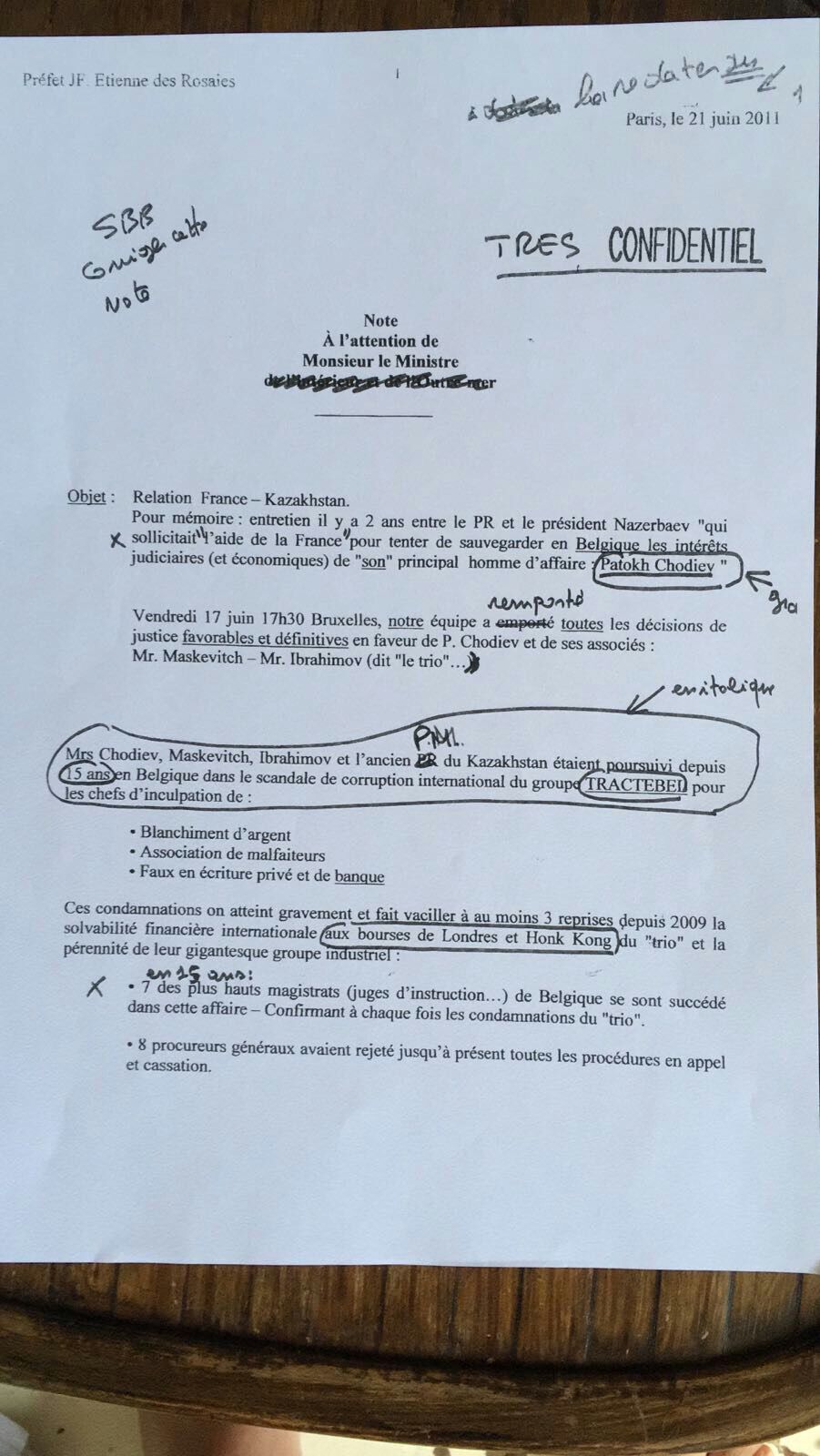

To try and prove this note’s authenticity, another note popped up, also signed by des Rosaies, this one dated 21 June 2011.

This new note is also written after the settlement between Chodiev and the Belgian prosecutors.

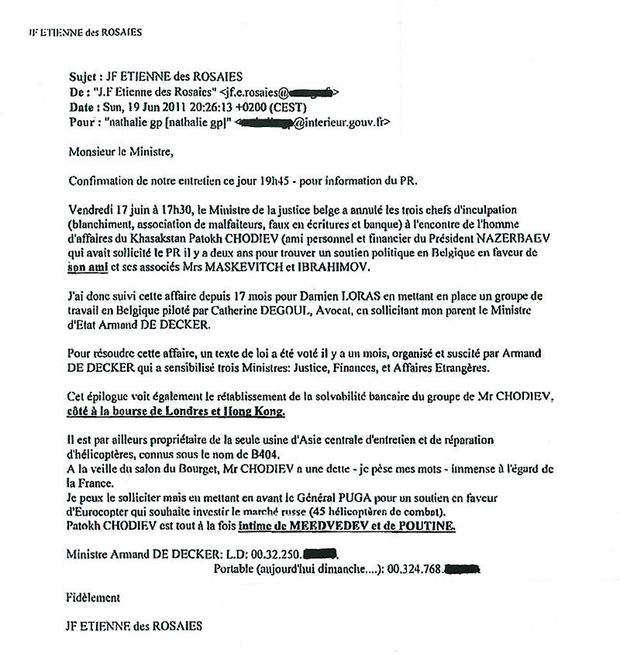

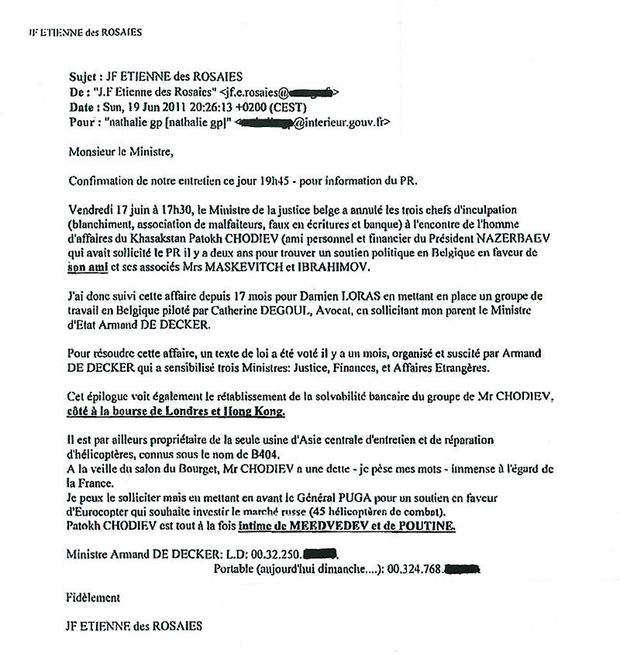

Finally, an email emerged, dated 19 June 2011, and also written by des Rosaies.

Apart from being written after the settlement between Chodiev and the prosecutors, like the other two previous documents, this email contains the false information that Chodiev is a close friend with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, and this information raises serious questions about the email’s credibility.

To sum it up, all the three documents attributed to Etienne des Rosaies are written after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). They are post-factum documents, and therefore it is very difficult to use them as a direct proof of a conspiracy.

Nothing in these documents prove that Chodiev’s lawyers (and particularly Armand De Decker) participated in the drafting of the law expanding the amicable settlements in Belgium, or interfered in any way with the legislative process.

On the contrary, everything in these documents looks like des Rosaies boasted about things he didn’t control, trying to place himself at the center of an operation that had nothing to do with him – something which is more in tune with what we know about his personality from both French and Belgian media.

Evidence from Claude Guéant

Apart from Etienne des Rosaies’ documents, the Belgian media published a document signed by the former French Minister of Home Affairs, Claude Guéant, praising Armand de Decker for his “wonderful job” on behalf of the Kazakh Trio. (see here:

http://www.levif.be/actualite/belgique/kazakhgate-le-courrier-qui-trahit-claude-gueant/article-normal-655107.html)

The document is dated 18 August 2011 – again, after the settlement between the Trio and the Belgian prosecutors – and is rather ambiguous. It may be read as a possible post-factum proof of a French interference in Belgium’s internal affairs, yet it may also be read as simply showing France’s interest in Chodiev and his associates.

The second interpretation is supported by Claude Guéant himself. He stated in front of the Kazakhgate commission that France was interested in a helicopter deal with Kazakhstan, and for this reason French authorities helped Patokh Chodiev with a lawyer – Catherin Degoul, who formed a defense team by recruiting Armand De Decker. And that was that, no interference took place. (see here:

http://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2017/05/04/a-bruxelles-claude-gueant-dement-etre-implique-dans-le-kazakhgate_5122203_3210.html)

With no other supplementary evidence, it is extremely difficult (if not totally impossible) to refute Guéant’s interpretation of events, simply because it’s logical and it fits everything else we know about the case. And hiring a French lawyer for a Belgian citizen violates no law.

Conclusions for Kazakhgate

To conclude, all the evidence available so far fails to prove a conspiracy aimed at helping Patokh Chodiev to change the criminal law in Belgium with assistance from France, for his own benefit.

The repeated publication of these documents in the Belgian media, often under the pretense of “new revelations,” doesn’t magically turn them into what they’re not. They fail to prove that the French authorities had anything to do with the drafting of the law regarding the extension of the amicable settlement, or that they intervened, directly or indirectly, in the legislative process on behalf of the Kazakh Trio.

All they prove is that France did indeed have an interest in Chodiev and his associates, and provided them with a legal defense team.

To make matters worse for the supporters of Kazakhgate, the settlement between Chodiev and Belgian prosecutors shows that the former was less interested in reaching a settlement than the Belgian authorities were.

According to the settlement, on 18 February 2011 the council chamber of the Court in Brussels decided that in the case concerning Chodiev and his partners the threshold of reasonable delay has been overstepped. As a consequence, as stated in the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure, if found guilty, the parties involved cannot be sentenced to jail, but only to a fine and confiscation of property.

In other words, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev knew for certain that, no matter what would eventually happen in the court, he would not go to jail. In the worst case for him, he would only have to pay a fine. To put it as plain as possible, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev was a free man: the threat of having to go to jail was gone. (see here for more information:

http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/kazakhgate-patokh-chodievs-settlement/)

So, on the one hand, we lack direct and solid proofs of a conspiracy benefitting Chodiev. Even the president of the Kazakhgate commission recognized that (see here:

http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/van-der-maelen-busts-kazakhgate-commission/).

On the other hand, we have plenty of direct proofs that the law expanding the amicable settlements was drafted and promoted by the diamond traders’ lobby in Antwerp and by the Belgian prosecutors themselves.

The Diamondgate evidence

The law from April 2011 didn’t come out of nowhere. The amendment first began to be discussed in 2008, among people close to the diamond traders in Anvers. Pressed by legislative changes and by a public opinion which was more and more unfavorable to the secrecy surrounding the trade in diamonds, the traders felt they have to fight back. Since a return to the old style of doing business was impossible, they began exploring ways to change the law so that they won’t end up in jail. (source:

http://blog.lesoir.be/docs/2012/07/26/jeu-judiciaire-autour-du-diamant-anversois/)

The Belgian investigative magazine Apache discovered in 2013 that the law extending the amicable settlement was drafted in 2009, under the auspices of the Attorney General of Anvers, Yves Liegeois.

The draft was written by Axel Haelterman and Raf Verstraeten, both law professors and lawyers working with the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), an umbrella foundation representing the interests of the diamond traders in Belgium.

Haelterman and Verstraeten were even invited by the Belgian Senate on 24 March 2011 to give their legal opinion on the amendment they themselves drafted two years ago. Unsurprisingly, their opinion on amendment 18 was positive. (source:

https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=publications/viewPub&COLL=S&PUID=83887104&TID=83887918&POS=1&LANG=fr)

The fact that the draft of the law was well-known and was widely circulated “for a long time” within political and judicial circles was also recognized by Stefaan De Clerck, who in 2011 was the Belgian Minister of Justice.

On 2 December 2010, a number of Belgian MPs founded “The Diamond Club,” an informal and secretive group aimed to offer parliamentarian support to the diamond traders in Anvers. The president of the Club was Jan Jambon, and the vice-presidents were Willem-Frederik Schiltz and Servais Verherstraeten. All the Flemish MPs were invited to join the club. “We want to unite in the “Diamantclub” all the politicians who defend the values and the interests of the diamond trade,” the invitation said. (source:

https://www.lachambre.be/kvvcr/showpage.cfm?section=qrva&language=fr&cfm=qrvaXml.cfm?legislat=54&dossierID=54-b026-900-0294-2014201502513.xml)

On 13 December 2010, Servais Verherstraeten, vice-president of “The Diamond Club,” introduced to the Chamber the law proposal aiming to expand the scope of the criminal transaction that was drafted by the diamond lobby and the prosecutors in Antwerp (source:

http://www.dekamer.be/FLWB/PDF/53/1252/53K1252001.pdf).

On 16 January 2012, AWDC issued a public statement in which the foundation recognized its role and congratulated itself for its “substantial contribution in the creation of new legislation extending the possibilities to conclude an amicable settlement.” (source:

http://www.hetgrotegeld.be/index.php/het_grote_geld/detail/1047)

Final conclusions

In July this year, the president of the inquiry commission investigating the extension of the amicable settlement, Dirk Van der Maelen, gave an interview to the Belgian magazine Knack.

“So behind the law extending the amicable settlement is not the billionaire Patokh Chodiev, but the diamond lobby?,” asked Knack’s Kristof Clerix and Peter Casteels.

Here’s Van der Maele’s answer: “At any rate, we have not been able to find anything that points to the interference of Armand De Decker or other people related to Chodiev in the legislative process. They did not come into action. The fathers of the law expanding the amicable settlement are the diamond sector and the College of General Prosecutors, under the political responsibility of the CD&V. At least until the end of 2009. Then the case was blocked. Then Haelterman met again with politicians, with the idea of linking the amicable settlement law to bank secrecy. This might surely have convinced the PS – a clever move coming from him. On 3 February 2011, the Council of Ministers decided to try and link the amicable settlement to banking secrecy.” (source:

http://www.knack.be/nieuws/belgie/dirk-van-der-maelen-over-kazachgate-ik-word-subtiel-gedwarsboomd/article-longread-873979.html)

And here lies the paradox. On the case regarding the extension of amicable settlements, we have two theories. One regards this extension as the result of a conspiracy where France interfered with Belgian authorities on behalf of Patokh Chodiev and his associates. This theory fails to bring solid evidence in its favor, yet it is highly circulated in the Belgian media.

The other theory regards the same extension as a result of the diamond traders’ lobby, and of the Belgian prosecutors’ need to devise a better instrument to help them fight corruption. This theory brings ample and solid direct evidence to support its claim, evidence that is recognized as such by the Kazakhgate commission. However, the Belgian media often tends to ignore it (or at least to downplay it).

For some reason or another, this looks like media manipulation.

The first problem with this note is its date. 28 June 2011 is after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). In other words, it is a post-factum document.

The other problem is that the note is considered a forgery by Armand De Decker and des Rosaies’ lawyers, so its authenticity cannot be proven beyond reasonable doubt. De Decker even has a written statement from des Rosaies saying that the note is a forgery.

To try and prove this note’s authenticity, another note popped up, also signed by des Rosaies, this one dated 21 June 2011.

The first problem with this note is its date. 28 June 2011 is after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). In other words, it is a post-factum document.

The other problem is that the note is considered a forgery by Armand De Decker and des Rosaies’ lawyers, so its authenticity cannot be proven beyond reasonable doubt. De Decker even has a written statement from des Rosaies saying that the note is a forgery.

To try and prove this note’s authenticity, another note popped up, also signed by des Rosaies, this one dated 21 June 2011.

This new note is also written after the settlement between Chodiev and the Belgian prosecutors.

Finally, an email emerged, dated 19 June 2011, and also written by des Rosaies.

This new note is also written after the settlement between Chodiev and the Belgian prosecutors.

Finally, an email emerged, dated 19 June 2011, and also written by des Rosaies.

Apart from being written after the settlement between Chodiev and the prosecutors, like the other two previous documents, this email contains the false information that Chodiev is a close friend with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, and this information raises serious questions about the email’s credibility.

To sum it up, all the three documents attributed to Etienne des Rosaies are written after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). They are post-factum documents, and therefore it is very difficult to use them as a direct proof of a conspiracy.

Nothing in these documents prove that Chodiev’s lawyers (and particularly Armand De Decker) participated in the drafting of the law expanding the amicable settlements in Belgium, or interfered in any way with the legislative process.

On the contrary, everything in these documents looks like des Rosaies boasted about things he didn’t control, trying to place himself at the center of an operation that had nothing to do with him – something which is more in tune with what we know about his personality from both French and Belgian media.

Evidence from Claude Guéant

Apart from Etienne des Rosaies’ documents, the Belgian media published a document signed by the former French Minister of Home Affairs, Claude Guéant, praising Armand de Decker for his “wonderful job” on behalf of the Kazakh Trio. (see here: http://www.levif.be/actualite/belgique/kazakhgate-le-courrier-qui-trahit-claude-gueant/article-normal-655107.html)

The document is dated 18 August 2011 – again, after the settlement between the Trio and the Belgian prosecutors – and is rather ambiguous. It may be read as a possible post-factum proof of a French interference in Belgium’s internal affairs, yet it may also be read as simply showing France’s interest in Chodiev and his associates.

The second interpretation is supported by Claude Guéant himself. He stated in front of the Kazakhgate commission that France was interested in a helicopter deal with Kazakhstan, and for this reason French authorities helped Patokh Chodiev with a lawyer – Catherin Degoul, who formed a defense team by recruiting Armand De Decker. And that was that, no interference took place. (see here: http://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2017/05/04/a-bruxelles-claude-gueant-dement-etre-implique-dans-le-kazakhgate_5122203_3210.html)

With no other supplementary evidence, it is extremely difficult (if not totally impossible) to refute Guéant’s interpretation of events, simply because it’s logical and it fits everything else we know about the case. And hiring a French lawyer for a Belgian citizen violates no law.

Conclusions for Kazakhgate

To conclude, all the evidence available so far fails to prove a conspiracy aimed at helping Patokh Chodiev to change the criminal law in Belgium with assistance from France, for his own benefit.

The repeated publication of these documents in the Belgian media, often under the pretense of “new revelations,” doesn’t magically turn them into what they’re not. They fail to prove that the French authorities had anything to do with the drafting of the law regarding the extension of the amicable settlement, or that they intervened, directly or indirectly, in the legislative process on behalf of the Kazakh Trio.

All they prove is that France did indeed have an interest in Chodiev and his associates, and provided them with a legal defense team.

To make matters worse for the supporters of Kazakhgate, the settlement between Chodiev and Belgian prosecutors shows that the former was less interested in reaching a settlement than the Belgian authorities were.

According to the settlement, on 18 February 2011 the council chamber of the Court in Brussels decided that in the case concerning Chodiev and his partners the threshold of reasonable delay has been overstepped. As a consequence, as stated in the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure, if found guilty, the parties involved cannot be sentenced to jail, but only to a fine and confiscation of property.

In other words, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev knew for certain that, no matter what would eventually happen in the court, he would not go to jail. In the worst case for him, he would only have to pay a fine. To put it as plain as possible, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev was a free man: the threat of having to go to jail was gone. (see here for more information: http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/kazakhgate-patokh-chodievs-settlement/)

So, on the one hand, we lack direct and solid proofs of a conspiracy benefitting Chodiev. Even the president of the Kazakhgate commission recognized that (see here: http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/van-der-maelen-busts-kazakhgate-commission/).

On the other hand, we have plenty of direct proofs that the law expanding the amicable settlements was drafted and promoted by the diamond traders’ lobby in Antwerp and by the Belgian prosecutors themselves.

The Diamondgate evidence

The law from April 2011 didn’t come out of nowhere. The amendment first began to be discussed in 2008, among people close to the diamond traders in Anvers. Pressed by legislative changes and by a public opinion which was more and more unfavorable to the secrecy surrounding the trade in diamonds, the traders felt they have to fight back. Since a return to the old style of doing business was impossible, they began exploring ways to change the law so that they won’t end up in jail. (source: http://blog.lesoir.be/docs/2012/07/26/jeu-judiciaire-autour-du-diamant-anversois/)

The Belgian investigative magazine Apache discovered in 2013 that the law extending the amicable settlement was drafted in 2009, under the auspices of the Attorney General of Anvers, Yves Liegeois.

The draft was written by Axel Haelterman and Raf Verstraeten, both law professors and lawyers working with the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), an umbrella foundation representing the interests of the diamond traders in Belgium.

Haelterman and Verstraeten were even invited by the Belgian Senate on 24 March 2011 to give their legal opinion on the amendment they themselves drafted two years ago. Unsurprisingly, their opinion on amendment 18 was positive. (source: https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=publications/viewPub&COLL=S&PUID=83887104&TID=83887918&POS=1&LANG=fr)

The fact that the draft of the law was well-known and was widely circulated “for a long time” within political and judicial circles was also recognized by Stefaan De Clerck, who in 2011 was the Belgian Minister of Justice.

On 2 December 2010, a number of Belgian MPs founded “The Diamond Club,” an informal and secretive group aimed to offer parliamentarian support to the diamond traders in Anvers. The president of the Club was Jan Jambon, and the vice-presidents were Willem-Frederik Schiltz and Servais Verherstraeten. All the Flemish MPs were invited to join the club. “We want to unite in the “Diamantclub” all the politicians who defend the values and the interests of the diamond trade,” the invitation said. (source: https://www.lachambre.be/kvvcr/showpage.cfm?section=qrva&language=fr&cfm=qrvaXml.cfm?legislat=54&dossierID=54-b026-900-0294-2014201502513.xml)

On 13 December 2010, Servais Verherstraeten, vice-president of “The Diamond Club,” introduced to the Chamber the law proposal aiming to expand the scope of the criminal transaction that was drafted by the diamond lobby and the prosecutors in Antwerp (source: http://www.dekamer.be/FLWB/PDF/53/1252/53K1252001.pdf).

On 16 January 2012, AWDC issued a public statement in which the foundation recognized its role and congratulated itself for its “substantial contribution in the creation of new legislation extending the possibilities to conclude an amicable settlement.” (source: http://www.hetgrotegeld.be/index.php/het_grote_geld/detail/1047)

Final conclusions

In July this year, the president of the inquiry commission investigating the extension of the amicable settlement, Dirk Van der Maelen, gave an interview to the Belgian magazine Knack.

“So behind the law extending the amicable settlement is not the billionaire Patokh Chodiev, but the diamond lobby?,” asked Knack’s Kristof Clerix and Peter Casteels.

Here’s Van der Maele’s answer: “At any rate, we have not been able to find anything that points to the interference of Armand De Decker or other people related to Chodiev in the legislative process. They did not come into action. The fathers of the law expanding the amicable settlement are the diamond sector and the College of General Prosecutors, under the political responsibility of the CD&V. At least until the end of 2009. Then the case was blocked. Then Haelterman met again with politicians, with the idea of linking the amicable settlement law to bank secrecy. This might surely have convinced the PS – a clever move coming from him. On 3 February 2011, the Council of Ministers decided to try and link the amicable settlement to banking secrecy.” (source: http://www.knack.be/nieuws/belgie/dirk-van-der-maelen-over-kazachgate-ik-word-subtiel-gedwarsboomd/article-longread-873979.html)

And here lies the paradox. On the case regarding the extension of amicable settlements, we have two theories. One regards this extension as the result of a conspiracy where France interfered with Belgian authorities on behalf of Patokh Chodiev and his associates. This theory fails to bring solid evidence in its favor, yet it is highly circulated in the Belgian media.

The other theory regards the same extension as a result of the diamond traders’ lobby, and of the Belgian prosecutors’ need to devise a better instrument to help them fight corruption. This theory brings ample and solid direct evidence to support its claim, evidence that is recognized as such by the Kazakhgate commission. However, the Belgian media often tends to ignore it (or at least to downplay it).

For some reason or another, this looks like media manipulation.

Apart from being written after the settlement between Chodiev and the prosecutors, like the other two previous documents, this email contains the false information that Chodiev is a close friend with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, and this information raises serious questions about the email’s credibility.

To sum it up, all the three documents attributed to Etienne des Rosaies are written after the Belgian parliament voted the law extending the possibility of amicable settlements (14 April 2011), and after the Kazakh Trio entered into a settlement with the Belgian prosecutors in Brussels (17 June 2011). They are post-factum documents, and therefore it is very difficult to use them as a direct proof of a conspiracy.

Nothing in these documents prove that Chodiev’s lawyers (and particularly Armand De Decker) participated in the drafting of the law expanding the amicable settlements in Belgium, or interfered in any way with the legislative process.

On the contrary, everything in these documents looks like des Rosaies boasted about things he didn’t control, trying to place himself at the center of an operation that had nothing to do with him – something which is more in tune with what we know about his personality from both French and Belgian media.

Evidence from Claude Guéant

Apart from Etienne des Rosaies’ documents, the Belgian media published a document signed by the former French Minister of Home Affairs, Claude Guéant, praising Armand de Decker for his “wonderful job” on behalf of the Kazakh Trio. (see here: http://www.levif.be/actualite/belgique/kazakhgate-le-courrier-qui-trahit-claude-gueant/article-normal-655107.html)

The document is dated 18 August 2011 – again, after the settlement between the Trio and the Belgian prosecutors – and is rather ambiguous. It may be read as a possible post-factum proof of a French interference in Belgium’s internal affairs, yet it may also be read as simply showing France’s interest in Chodiev and his associates.

The second interpretation is supported by Claude Guéant himself. He stated in front of the Kazakhgate commission that France was interested in a helicopter deal with Kazakhstan, and for this reason French authorities helped Patokh Chodiev with a lawyer – Catherin Degoul, who formed a defense team by recruiting Armand De Decker. And that was that, no interference took place. (see here: http://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2017/05/04/a-bruxelles-claude-gueant-dement-etre-implique-dans-le-kazakhgate_5122203_3210.html)

With no other supplementary evidence, it is extremely difficult (if not totally impossible) to refute Guéant’s interpretation of events, simply because it’s logical and it fits everything else we know about the case. And hiring a French lawyer for a Belgian citizen violates no law.

Conclusions for Kazakhgate

To conclude, all the evidence available so far fails to prove a conspiracy aimed at helping Patokh Chodiev to change the criminal law in Belgium with assistance from France, for his own benefit.

The repeated publication of these documents in the Belgian media, often under the pretense of “new revelations,” doesn’t magically turn them into what they’re not. They fail to prove that the French authorities had anything to do with the drafting of the law regarding the extension of the amicable settlement, or that they intervened, directly or indirectly, in the legislative process on behalf of the Kazakh Trio.

All they prove is that France did indeed have an interest in Chodiev and his associates, and provided them with a legal defense team.

To make matters worse for the supporters of Kazakhgate, the settlement between Chodiev and Belgian prosecutors shows that the former was less interested in reaching a settlement than the Belgian authorities were.

According to the settlement, on 18 February 2011 the council chamber of the Court in Brussels decided that in the case concerning Chodiev and his partners the threshold of reasonable delay has been overstepped. As a consequence, as stated in the Belgian Code of Criminal Procedure, if found guilty, the parties involved cannot be sentenced to jail, but only to a fine and confiscation of property.

In other words, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev knew for certain that, no matter what would eventually happen in the court, he would not go to jail. In the worst case for him, he would only have to pay a fine. To put it as plain as possible, from 18 February 2011 Chodiev was a free man: the threat of having to go to jail was gone. (see here for more information: http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/kazakhgate-patokh-chodievs-settlement/)

So, on the one hand, we lack direct and solid proofs of a conspiracy benefitting Chodiev. Even the president of the Kazakhgate commission recognized that (see here: http://www.opensourceinvestigations.com/belgium/van-der-maelen-busts-kazakhgate-commission/).

On the other hand, we have plenty of direct proofs that the law expanding the amicable settlements was drafted and promoted by the diamond traders’ lobby in Antwerp and by the Belgian prosecutors themselves.

The Diamondgate evidence

The law from April 2011 didn’t come out of nowhere. The amendment first began to be discussed in 2008, among people close to the diamond traders in Anvers. Pressed by legislative changes and by a public opinion which was more and more unfavorable to the secrecy surrounding the trade in diamonds, the traders felt they have to fight back. Since a return to the old style of doing business was impossible, they began exploring ways to change the law so that they won’t end up in jail. (source: http://blog.lesoir.be/docs/2012/07/26/jeu-judiciaire-autour-du-diamant-anversois/)

The Belgian investigative magazine Apache discovered in 2013 that the law extending the amicable settlement was drafted in 2009, under the auspices of the Attorney General of Anvers, Yves Liegeois.

The draft was written by Axel Haelterman and Raf Verstraeten, both law professors and lawyers working with the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), an umbrella foundation representing the interests of the diamond traders in Belgium.

Haelterman and Verstraeten were even invited by the Belgian Senate on 24 March 2011 to give their legal opinion on the amendment they themselves drafted two years ago. Unsurprisingly, their opinion on amendment 18 was positive. (source: https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=publications/viewPub&COLL=S&PUID=83887104&TID=83887918&POS=1&LANG=fr)

The fact that the draft of the law was well-known and was widely circulated “for a long time” within political and judicial circles was also recognized by Stefaan De Clerck, who in 2011 was the Belgian Minister of Justice.

On 2 December 2010, a number of Belgian MPs founded “The Diamond Club,” an informal and secretive group aimed to offer parliamentarian support to the diamond traders in Anvers. The president of the Club was Jan Jambon, and the vice-presidents were Willem-Frederik Schiltz and Servais Verherstraeten. All the Flemish MPs were invited to join the club. “We want to unite in the “Diamantclub” all the politicians who defend the values and the interests of the diamond trade,” the invitation said. (source: https://www.lachambre.be/kvvcr/showpage.cfm?section=qrva&language=fr&cfm=qrvaXml.cfm?legislat=54&dossierID=54-b026-900-0294-2014201502513.xml)

On 13 December 2010, Servais Verherstraeten, vice-president of “The Diamond Club,” introduced to the Chamber the law proposal aiming to expand the scope of the criminal transaction that was drafted by the diamond lobby and the prosecutors in Antwerp (source: http://www.dekamer.be/FLWB/PDF/53/1252/53K1252001.pdf).

On 16 January 2012, AWDC issued a public statement in which the foundation recognized its role and congratulated itself for its “substantial contribution in the creation of new legislation extending the possibilities to conclude an amicable settlement.” (source: http://www.hetgrotegeld.be/index.php/het_grote_geld/detail/1047)

Final conclusions

In July this year, the president of the inquiry commission investigating the extension of the amicable settlement, Dirk Van der Maelen, gave an interview to the Belgian magazine Knack.

“So behind the law extending the amicable settlement is not the billionaire Patokh Chodiev, but the diamond lobby?,” asked Knack’s Kristof Clerix and Peter Casteels.

Here’s Van der Maele’s answer: “At any rate, we have not been able to find anything that points to the interference of Armand De Decker or other people related to Chodiev in the legislative process. They did not come into action. The fathers of the law expanding the amicable settlement are the diamond sector and the College of General Prosecutors, under the political responsibility of the CD&V. At least until the end of 2009. Then the case was blocked. Then Haelterman met again with politicians, with the idea of linking the amicable settlement law to bank secrecy. This might surely have convinced the PS – a clever move coming from him. On 3 February 2011, the Council of Ministers decided to try and link the amicable settlement to banking secrecy.” (source: http://www.knack.be/nieuws/belgie/dirk-van-der-maelen-over-kazachgate-ik-word-subtiel-gedwarsboomd/article-longread-873979.html)

And here lies the paradox. On the case regarding the extension of amicable settlements, we have two theories. One regards this extension as the result of a conspiracy where France interfered with Belgian authorities on behalf of Patokh Chodiev and his associates. This theory fails to bring solid evidence in its favor, yet it is highly circulated in the Belgian media.

The other theory regards the same extension as a result of the diamond traders’ lobby, and of the Belgian prosecutors’ need to devise a better instrument to help them fight corruption. This theory brings ample and solid direct evidence to support its claim, evidence that is recognized as such by the Kazakhgate commission. However, the Belgian media often tends to ignore it (or at least to downplay it).

For some reason or another, this looks like media manipulation.

Trackbacks and Pingbacks