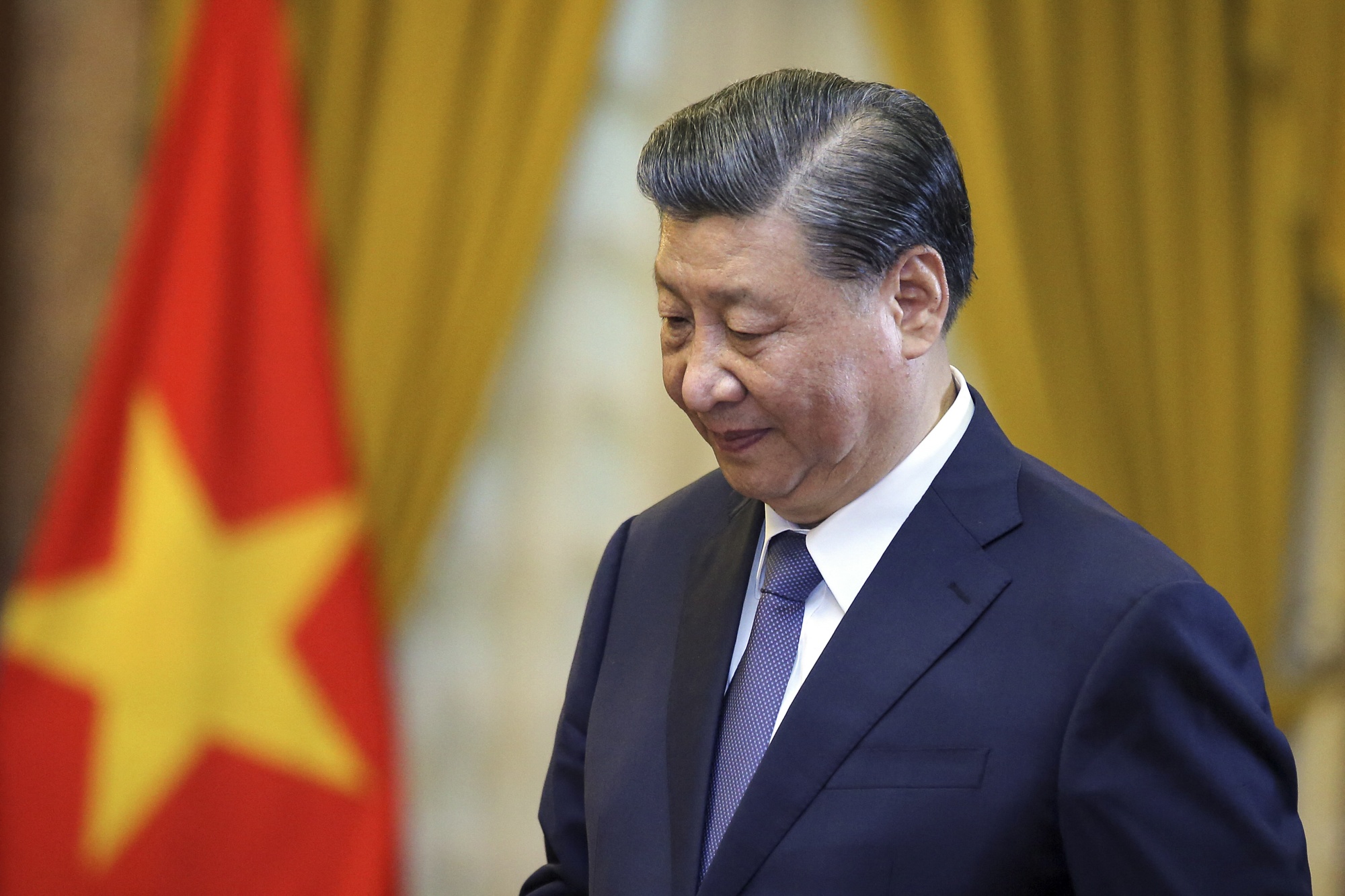

President Xi Jinping vowed to deepen an anti-corruption campaign spanning several critical sectors, a move that risks freezing spooked decision makers and hampering China’s fragile economic recovery, according to Bloomberg.

The Chinese leader singled out the finance, energy, pharmaceutical and infrastructure sectors, as well as state-owned enterprises, as targets of fresh scrutiny at a meeting of the Communist Party’s anti-graft agency on Monday, according to state media.

China will clean up “hidden risks” in sectors where “power is concentrated, capital is intensive and resources are rich,” Xi told the conclave, state broadcaster China Central Television reported. “There’s no turning back, no relaxing and no mercy in fighting corruption,” he said.

Xi’s comments put vast swathes of the economy on notice for more turmoil ahead, potentially undermining his efforts to bolster investor confidence and arrest a growth slowdown. The president is performing a balancing act as he tries to cement the party’s control, while wooing overseas executives to back the world’s second-largest economy.

Looking tough on corruption is important because some cases concern security, said Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia Pacific economist at Natixis SA. The measures are damaging confidence and the economy but they’re unlikely to stop soon, she added.

“There is a real trade-off in Xi’s eyes and security simply comes first since it is binary,” Herrero said.

China’s onshore stocks traded up 0.3% as of the mid-day break, trailing the advance in a broader gauge of Asian equities. The benchmark CSI 300 Index had been declining in the previous five sessions and slumped to its lowest in nearly five years on Monday amid persistent growth concerns.

China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong has made corruption his signature policy since coming to power more than a decade ago. A record number of senior officials — known as “tigers” — were ensnared last year, when China investigated more than 100 financial professionals including former Bank of China Ltd. chairman Liu Liange. Xi said on Monday that “ants” were also in his crosshairs.

The other sectors Xi cast suspicion over are no strange to graft probes. The $1.4 trillion health care industry was rocked by probes last year, with hospital officials accused of accepting bribes and doctors ordered to surrender any illicit income.

In 2020, the energy universe was put under the spotlight, when Xi ordered retrospective investigation in the autonomous Inner Mongolia region’s coal sector that snared 1,163 officials. And this week’s meeting came as a state media documentary highlighted an official who loaded more than 150 billion yuan ($21 billion) onto his city’s debt books in “vanity” infrastructure projects.

Still, officials risk destabilizing entire sectors if they move too suddenly, said Dominic Chiu, senior analyst at Eurasia Group. “Authorities will have to carry out their campaigns delicately to not introduce too much uncertainty at a time when confidence-building is crucial for the economy,” he said.

The Chinese gaming watchdog’s abrupt proposal of curbs last month sparked an $80 billion selloff in some of China’s biggest online names including Tencent.

Punishments for those found guilty of offering bribes will be severe, Xi declared on Monday, emphasizing that those instigating the doling out of inappropriate funds would be just as culpable as those receiving them. The graft situation remains “complex and challenging,” he added.

China has also purged some 15 members from the upper echelons of its military and defense-industrial complex in recent months, as a corruption probe roils that sector. Those moves come after Beijing ousted its foreign minister abruptly over the summer without explanation, creating further instability.

Investors have complained that China is becoming a black box amid the abrupt purges and an intensifying national security campaign. Authorities probed consultancy firms, expanded a vague anti-spy law and restricted access to data last year.

In that environment, two official measures of foreign direct investment into China fell to record lows in 2023, with one marking its first contraction.

“The security-centric economic thinking is indeed a risk,” Shirley Yu, fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center, told Bloomberg TV on Tuesday from a conference in Shanghai. “Economic policy is to a large extent driven by fear,” due to a mindset that stems from US-China geopolitical tensions and is present in both nations, she added.

Trackbacks and Pingbacks